Trivia about the Great Achievers in Philippine Art

The range of subjects in Philippine contemporary painting can be as wide and varied as the artist’s imagination. Even scenes that appear “typical” may be re-interpreted and given new treatment. How often have we encountered landscape paintings with churches, or images of jeepney’s, women in groups. or sidewalk vendors? And yet. it is the frequency of their occurrences that help define local vignettes” It is the artist’s task to etch them into public memory in ways that are creative and fresh, From the Cultural Center of the Philippines visual arts collection, we are pleased to present a selection of paintings that may be viewed as contemporary renditions of folk scenes: (followed by particulars of each painting artist, title, mention the subject matter, and medium and size in parenthesis.

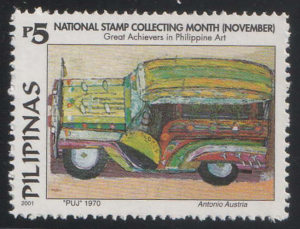

Antonio Austria (b. 1936) paints with love and irony Filipinos of the working class. He draws the sari-sari store women tending their smoked sardine still-life’s; vendors surrounded by their woven baskets of glutinous rice cakes; the macho jeepney driver and his passengers of office clerks; a family in its one room shanty; the balloon man; the love-struck suitor standing under his maiden’s window; and other vignettes of ordinary Filipino life Austria’s images are flat. simplified and distorted. The figures are squat and dumpy, drawn in heavy outline and in caricature which resembles a child’s drawing. Yet they have a scale of their own and a sense of their own reality. The figure are lost in a wild array of objects against flat backgrounds. Lines and color are used to suggest a mood or create emotional impact. Austria makes use of color in its full range. This liking for bright colors enhances Austria’s image as a naive painter.

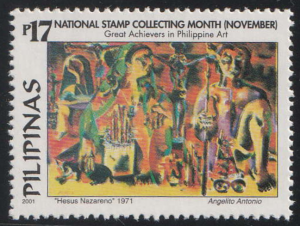

Angelito Antonio (b. 1936) is a second generation Neo-Realist. He works in the cubist manner of Vicente Manansala without the latter’s fragmentation of forms. The appeal of his figures stems from their geometric quality. Black lines outline color modulations and transparencies within the divided planes. His subjects are genre scenes focusing on traditional folk occupation and activities.

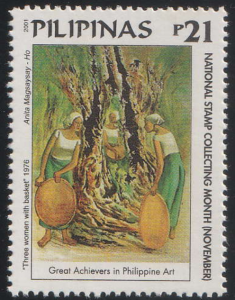

Anita Magsaysay-Ho (b. 1914) had her way of rendering subject matter that has become her hallmark in over three decades: peasant women working in the fields, mending nets, feeding the chicken, cooking, gossiping, they are invariably thin with elongated necks, slant eyes, hair wrapped in bandanas torso, hips, arms and legs bent at a sharp angle. Here women of the fifties have a distinctive slick look, radiating contentment and a sense of well-being especially those she did in egg tempera, a medium in which she produced her finest and most memorable work. The slickness of her egg temperas derives from her meticulously tidy brushwork as much as an elaborate technique of applying layers of paint and glazes one on top of another.

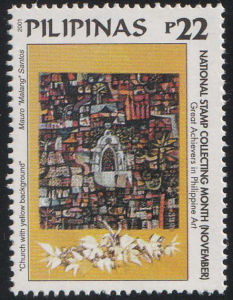

MauroMalang Santos (b. 1928) began as a newspaper cartoonist and illustrator in 1947, when he was aged 19. He later became known for two popular comic-strip characters. Only in 1967 did his transformation take place from lighthearted illustrator to full-fledged painter. Malang’s universe is organized in clusters or groups, strategically arranged in the space of a town plaza. In the background looms a Gothic church. The acacia tree on the church ground is another conventional landmark. Clusters of people are involved in different activities; yet all are part of the total picture, contributing to the momentum as well as to the mood of the scene. This microcosm of Philippine life has become the classic Malang genre.

This series was soon followed by cityscapes – of urban shanties, houses, high-rises, church, flowers, birds and religious icons. Malang’s landscapes are made up of composed images of varying geometric forms and sizes, arranged into well-ordered, overlapping planes. The whole forms a band of color{ul forms across the canvas. The resulting architecture, precise and finely drawn is a touch of elegance completely divorced from the brutal social realities of Philippine actuality. Above this deliberately arranged jumble of forms is the empty expanse of sky, in bold and intense colors, depending on the time of day. The contrast between these two levels is defined by the arbitrary horizon drawn just above the architectural line.

Like his landmark tree, Malang’s sky is punctuated by a simplified geometric shape – by a celestial body, either sun or moon. The painter uses the same basic approach in composing his cityscapes as he does his town plaza scenes. Each geometric form seems independent; yet it is interlocked with other forms to complete the picture. The range of imagery that preoccupies Malang – venders, trees, flora, birds, sun-moon, churches – recurs in different variations as the motifs of his paintings. These motifs are superimposed on the open window spaces of the architecture of interspersed with the interlocking geometric forms. This gives his painting a quaint folk-baroque atmosphere.

Toward the late sixties and the early seventies, Malang’s paintings acquired a greater sense of freedom. The forms became more stylized, simpler and less crowded. The sense of scale and proportion became bolder and of greater dimension; the composition more complex; the texture softer and more tactile. Despite his architectural abstractions, Malang – like his friend and contemporary Ang Kiukok – follows the figurative tradition oi his master, Manansala. The three seem absorbed in their repertoire of Philippine motifs. interesting that these three artists – colorists all – should use color to project their visual concepts and emotions. From this common ground they went off in three different directions, each to develop his own personal style.

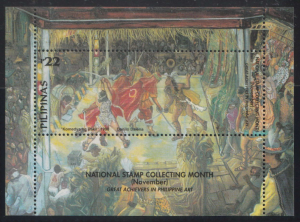

Danilo Dalena (b. 1942) stared out by painting an unsanitized view of life and times at persistence level. He began with what he called the kubeta (“toilet”) series – etchings that take off from the graffiti in a beer house toilet. Dalena’s Jai-Alai series, which he painted from 1974 until the late seventies, used the local betting hall as a metaphor for the human condition. His glistening bodies stand in attitudes of hope and despair; occasionally they rejoice at a hit. Dalena’s Alibangbang series is based on the artist’s observation of life in a Metro Manila beer house of that name. From that cramped, upstairs room which stank of sweaty clothes, Dalena lifted the spirit and memorialized touching human moments out of the welter of noise, lust, squalor, flamboyant vulgarity and humor.

Dalena uses strong contrasts to add a surrealistic drama to his painting Earth colors that are distinctly urban become even more intense because they are set off by light and dark. Dalena’s paintings have a sense of the epic because of the number of lumpy figures that he manages to squeeze within his frame to experience a Dalena painting is to enter the chaotic composition of moving breathing vibrating humanity – seen only through highlighted limbs and featureless faces. images swirl yet remain compact and concentrated with precarious balance. His single-figure compositions have the bulk and weight of monuments. Dalena’s work is humorous, sensitive and wonderfully observant.

Recent Comments